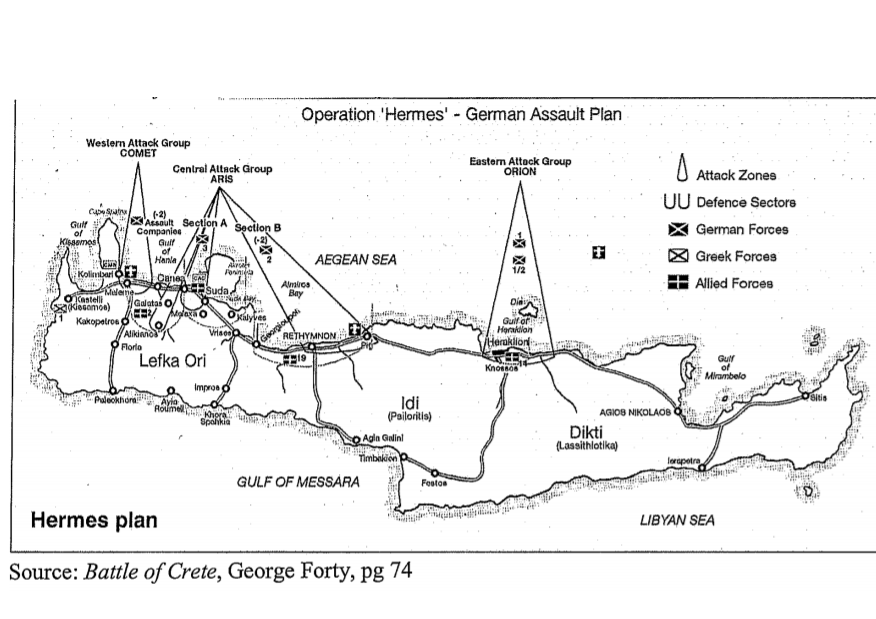

May 20th 1941: The German invasion begins

On 20 May 1941 the Germans activated the operation “Mercury”. Landing among or near concealed the allies defensive positions, the paratroops and the glider’s staff suffered extremely heavy casualties. Survivors of the battle managed to establish a foothold on the island, but at the end of the first day the German position was still very tenuous.

Maleme sector – The airfield and the hill 107

The invasion began with the first light of May 20th with a heavy bombardment by the German air force. For the allied forces on Crete – who had endured daily air attacks since the end of April – the arrival of German aircraft promised just one more day of bombing. Around 7.30 am there was a stop in the attack, during which a lot of men prepared to have breakfast. Before they had a chance to eat, a more intense air bombardment began. Soon after 8 am gliders began to appear in the sky – the first sign that something significant was happening. German paratroopers, jumping out of dozens of Junkers Ju 52 aircraft, landed near Maleme Airfield and the town of Chania. The sky above Chania was soon filled with a multitude of colored parachutes. It was the the West Group under the code-name “Comet” with its commander Generalmajor Eugen Meindl. From the defender’s side, the 21st, 22nd and 23rd New Zealand battalions held Maleme Airfield and the area around. The Germans suffered many casualties in the first hours of the invasion, a company of III Battalion, 1st Assault Regiment lost 112 killed out of 126 men and 400 of 600 men in III Battalion were killed on the first day.

Generalmajor Eugen Meindl (Photo by en.wikipedia.org)

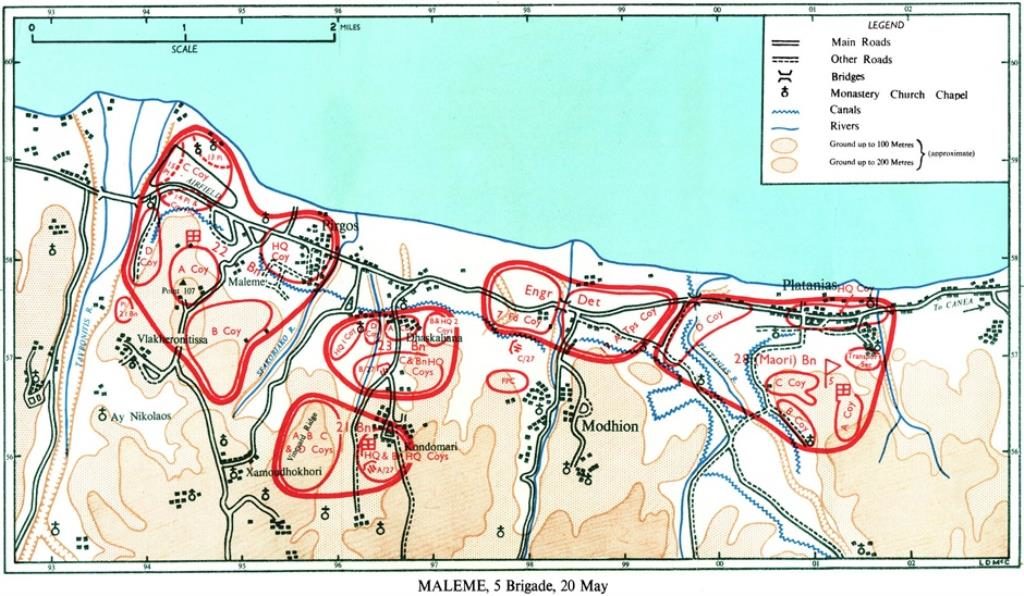

Defending the Maleme sector was 5th (NZ) Brigade. Commanded by Brigadier James Hargest, this comprised the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, and 28th (Maori) Battalions, an engineer detachment, three troops of artillery, and the New Zealand Field Punishment Centre.

The map of Maleme and Platanias area (Photo by nzhistory.govt.nz)

Located around the perimeter of the airfield were 22nd Battalion and two companies of the 27th (Machine Gun) Battalion. To the east of Maleme, 23rd Battalion was positioned along the road at right angles to the coast. Paratroops landed among their positions on 20 May. The battalion spent the morning patrolling and mopping up isolated German troops. The under-strength 21st Battalion was located to the south of 23rd Battalion. Very few paratroops landed in this area.

The legendary 28th (Maori) Battalion was positioned around the village of Platanias to cover the beach and the main road. The battalion saw little early action, although a German glider and troop carrier crash-landed in D Company’s area. That evening B Company went off to help 22nd Battalion at Maleme. Aside from this, the day was spent mostly in mopping up and patrolling.

The 7th Field Company, the Engineers, was stationed to the east of 23rd Battalion. Around 150 paratroops landed on their west flank and were killed on the way down or mopped up shortly after landing. The 19th Army Troops Company, New Zealand Engineers, was stationed between 7th Field Company and 28th (Maori) Battalion. They only received a few paratroops.

The Field Punishment Centre (FPC) was located south of 7th Field Company about 900 m to the west of the village of Modhion. The FPC was a detention center for Allied troops who had broken military rules on Crete. German paratroops dropped in large numbers all through the FPC area. Most were killed or captured. Soldiers at the FPC spent the rest of the day dealing with snipers, evacuating enemy prisoners and wounded, and collecting equipment from canisters dropped by the Germans. A, B and C Troops of the 27th Battery, 5th New Zealand Field Regiment, were stationed east of Maleme. Equipped with two 3.7-inch howitzers and seven 75-mm guns, the New Zealand gunners shelled enemy positions and themselves came under fire. They were also involved in small-arms skirmishes with paratroops. The 5th Brigade Headquarters was located at Platanias when the invasion began. Brigadier Hargest returned to his battle headquarters with some difficulty and was able to observe Maleme airfield from there.

Brigadier James Hargest (Photo by www.radionz.co.nz)

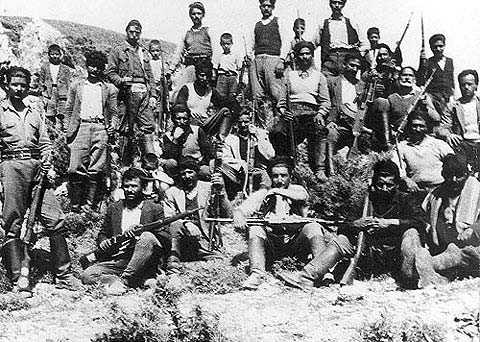

Many paratroops died before they reached the ground while others were hit as they struggled to remove their cumbersome parachute harnesses. Cretans too became involved in the battle. Local villagers, armed with shotguns, axes and spades, attacked paratroops who landed near their homes. The Cretan population would later suffer terrible reprisals from the German occupation force for these actions.

Members of the Cretan resistance (Photo by www.gtp.gr)

Initial fighting was confined to the areas around Maleme and Chania–Galatas. About 50 gliders came down around Maleme – mainly along the dry Tavronitis riverbed. Paratroops were also dropped to the west, south and east of the Maleme airfield, with orders to seize control of the airfield and high ground overlooking it. Those who landed to the south and east came down amongst New Zealand units and were cut to pieces. It was a different story west of the airfield. Most of the gliders had managed to land safely in an area that could not be observed by defenders on the higher ground. A substantial number of paratroops had also dropped in and around the Tavronitis riverbed – an area Freyberg had left undefended. These troops wasted little time in reorganising themselves and were soon threatening the airfield.

Defending the key positions at Maleme was 22nd Battalion. Under the command of First World War Victoria Cross (VC) winner Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew, the battalion occupied positions along the western edges of the airfield as well the substantial hill – known as Point 107 – overlooking it. By the afternoon the situation was serious enough for Andrew to seek additional support from 23rd Battalion, located to his east. This request was turned down by Brigadier James Hargest, who mistakenly believed 23rd Battalion was tied up dealing with enemy paratroops in its area.

Lieutenant-Colonel Leslie Andrew (Photo by en.wikipedia.org)

In desperation Andrew decided to use his meager reserve – two tanks and an infantry platoon – to drive the Germans back from the edge of the airfield. But the counter-attack petered out when the tanks broke down. Unable to contact his forward companies and fearing that the rest of the battalion would be cut off, Andrew decided to pull back from Point 107 to a nearby ridge. Hargest agreed to the withdrawal – famously replying, ‘if you must, you must’ – before ordering two companies forward to reinforce 22nd Battalion. One of these companies briefly reoccupied Point 107 before falling back, while the other failed to make contact in the dark and also withdrew. Andrew pulled his battalion back to link up with 21st Battalion in the east, leaving behind two forward companies fighting on the western edge of the airfield. Both companies managed to extricate themselves when they found that the rest of the battalion had withdrawn.

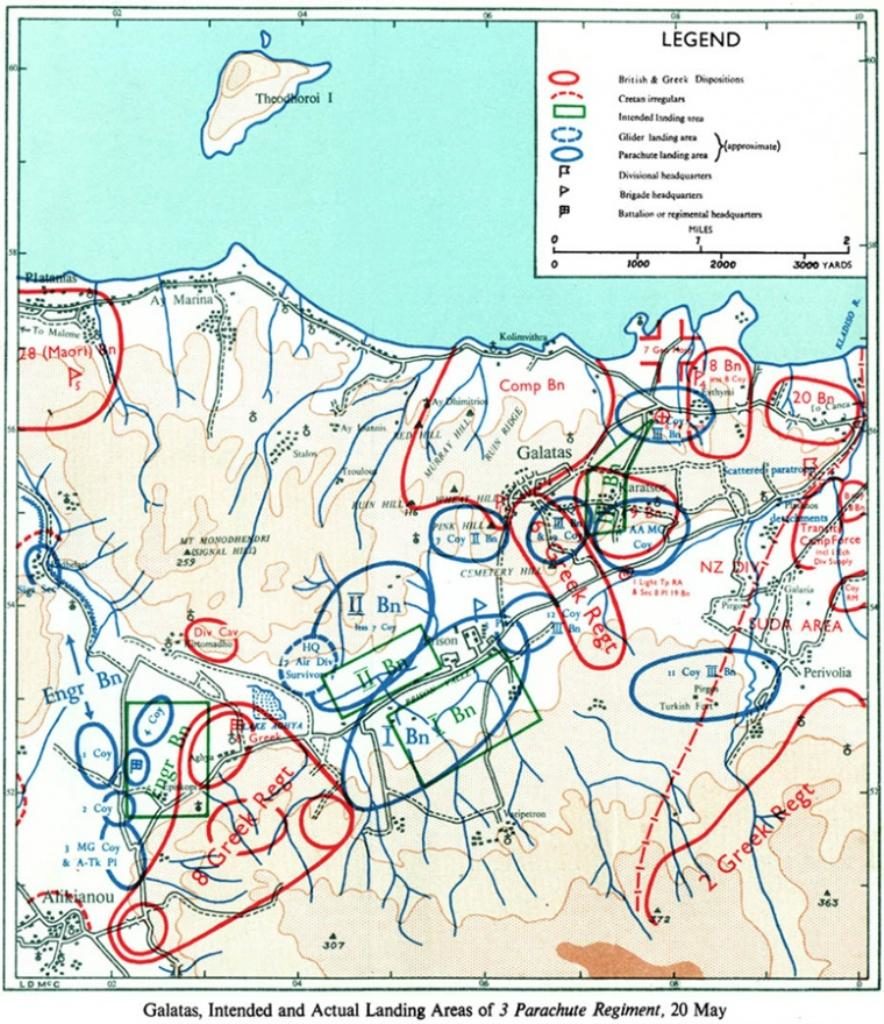

Galatas and Prison valley sector

In the Galatas area, the German attack started with a glider assault. Glider-borne troops landed near Chania but were unable to achieve their main objectives – the capture of Chania and Souda – and were forced to surrender a few days later. It was the Center Group (7th Air Division) with the code-name “Mars” or “Aris” under the command of Generalmajor Wilhelm Süssmann. German casualties during this operation were appalling as many of the gliders were shot down or wrecked on landing. Among those killed was also Sussmann.

General Wilhelm Sussmann, 7th Air Div. commander (Photo by http://thefifthfield.com)

The main concentration of German landings in this sector occurred in an area known as Prison Valley, south of Galatas. Two battalions of paratroops dropped astride the Chania–Alikianos road managed to establish a foothold around the Ayia Prison complex. Their presence threatened communications with 5th Brigade in the east and it became obvious that a strong counter-attack was needed.

The map of Galatas and Ayia (prison valley) area (Photo by nzhistory.govt.nz)

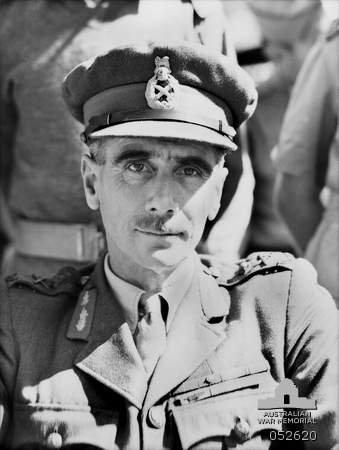

Responsibility for the defense of the Galatas area lay with the 10th (NZ) Brigade, led by Colonel Howard Kippenberger. The brigade comprised the 6th and 8th Greek Regiments, a Composite Battalion, and New Zealand Divisional Cavalry.

Colonel Howard Kippenberger (Photo by en.wikipedia.org)

The 6th Greek Regiment was stationed along the Prison–Galatas road and across the valley from a Turkish fort. Poorly armed and with little ammunition, they were forced back to 19th Battalion’s position following a concerted attack by the Germans. The 8th Greek Regiment, stationed in the area around Alikianos, was initially cut off from other units and threatened by the Germans. They held on all day, inflicting severe casualties on the German paratroops in their area. Most of the New Zealanders attached to the regiment were captured.

The Composite Battalion consisted of three main groups. The Reserve Mechanical Transport Group was between the coast and the northern slopes of Red Hill. Two companies of gunners from the 4th New Zealand Field Regiment and men from the Divisional Supply Company were stationed on Red Hill and Ruin Hill. Few Germans landed in this area on 20 May and these groups spent most of the day patrolling. The third group was a mixture of men from the 5th New Zealand Field Regiment on Wheat Hill and the Divisional Petrol Company stationed on Pink Hill. This group was poorly armed and the men, mainly drivers and technicians, had little infantry experience. After bravely fighting off several heavy attacks they were forced to withdraw to Wheat Hill late in the afternoon. New Zealand Divisional Cavalry, whose initial position was isolated, were moved just before dusk to fill in the gap between Pink Hill and Cemetery Hill. This redeployment filled a weak spot in the defenses and ensured that the worst crisis of the day was over.

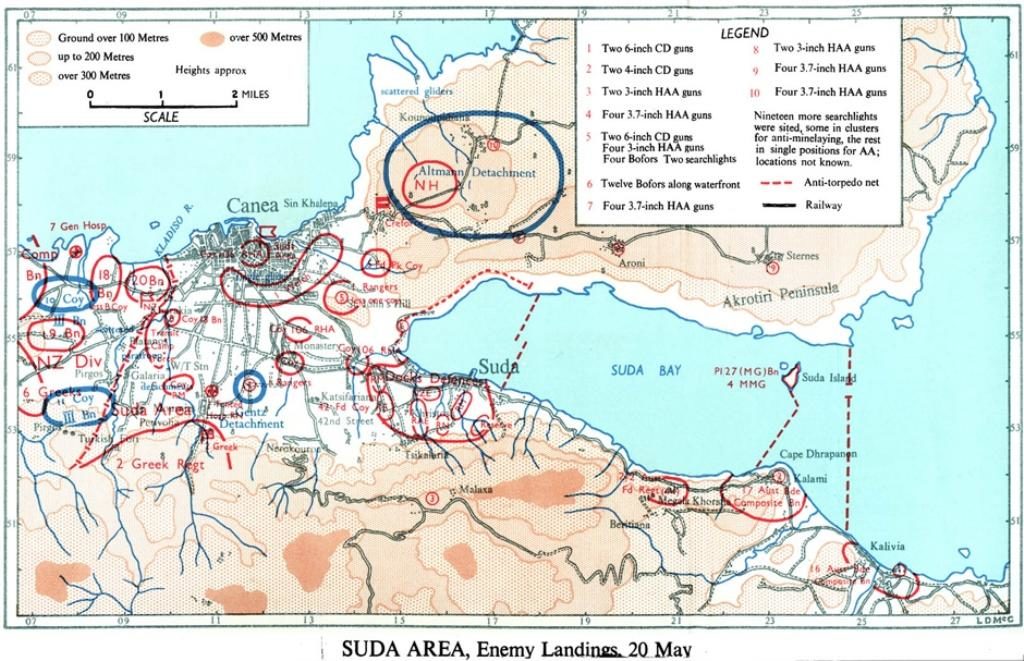

Chania town and Souda bay sector

Defending also Chania area was Colonel Howard Kippenberger’s 10th (NZ) Brigade and the 4th (NZ Brigade), commanded by Brigadier Lindsay Inglis. Kippenberger quickly realized that his exhausted composite brigade was in no shape to mount such an operation. At 4th (NZ) Brigade HQ, Brigadier Inglis came to the same conclusion – he believed an attack by his brigade would clear the Germans from the Prison Valley and place it in a position to assist at Maleme. Freyberg rejected the idea and Inglis was ordered instead to mount a single-battalion attack. Two companies of 19th Battalion and three British light tanks set off, but made no significant progress and eventually withdrew.

Brigadier Lindsay Inglis (Photo by en.wikipedia.org)

Chania and Souda areas were defended by the 4th (NZ Brigade). This comprised the 18th, 19th and 20th Battalions, 2nd Greek Regiment, and ancillary units. 18th Battalion, minus one company which had escorted the King of Greece to Perivolia the previous day, was stationed along the Chania–Maleme road near the coast and the 7th (British) General Hospital. They spent the day mopping up isolated German troops.

The map of Chania town and Souda area (Photo by nzhistory.govt.nz)

The 19th Battalion had around 200 paratroops land in their area, south-east of Galatas. Most were killed, and by mid-morning all companies were reporting that the area was clear of enemy troops. The 2nd Greek Regiment, with a party of New Zealand instructors attached, fended off paratroops which landed in its area, despite a severe lack of ammunition. The Greeks received support later in the day from an Australian battalion which arrived from Georgeoupolis.

The 6th (New Zealand) Field Ambulance and 7th (British) General Hospital were subjected to a severe bombing and strafing attack which lasted around 90 minutes. Following the air attack, German paratroops landed and took over the hospital. At midday, the prisoners were ordered to move towards Galatas. They were rescued by troops from 19th Battalion after some fighting. Four 3.7-inch howitzers of 1st Light Troop, Royal Artillery were situated to the south of the Chania–Alikianos road. Despite support from a section of infantry from 19th Battalion, their position was overrun by paratroops and they withdrew with heavy losses.

At the end of the day, the Germans’ foothold on the island was tenuous. Two waves of airborne troops had failed to secure the airfields or the port facility at Souda Bay. Though there had been small gains at Maleme, the second wave of German paratroops dropped near Rethimnon and Heraklion had met strong resistance and made no progress. German commanders in Athens feared the worst – that they had severely underestimated the number of defenders on Crete and were about to suffer a humiliating defeat.

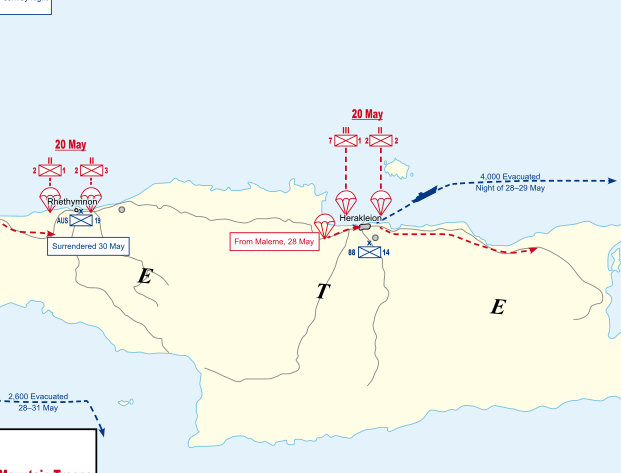

Rethymno–Heraklion sectors

A second wave of German transports supported by Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica attack aircraft, arrived in the afternoon, dropping more paratroopers and gliders containing assault troops. One group, part of “Mars” (or “Aris”) under Süssmann’s command attacked at Rethymnon at 16:15. The area Retymnon defended by Brigadier G. A. Vasey commanding Australian and Greek units totaling 7,500 men.

Brigadier George Alan Vasey

The East Group with the code-name “Orion” under the command of Colonel Bruno Bräuer attacked at Heraklion at 17:30, where the defenders were waiting and inflicted many casualties.

Colonel Bruno Bräuer (Photo by ww2gravestone.com)

Heraklion was defended by the 14th Infantry Brigade, the 2/4th Australian Infantry Battalion and the Greek 3rd, 7th and “Garrison” (ex-5th Crete Division) battalions under the command of Brigadier B.H. Chappell. The Greeks lacked equipment and supplies, particularly the Garrison Battalion. The Germans pierced the defensive cordon around Heraklion on the first day, seizing the Greek barracks on the west edge of the town and capturing the docks, the Greeks counter-attacked and recaptured both points. The Germans dropped leaflets threatening dire consequences if the Allies did not surrender immediately. The next day, Heraklion was heavily bombed and the depleted Greek units were relieved and assumed a defensive position on the road to Knossos.

As night fell, none of the German objectives had been secured. Of 493 German transport aircraft used during the airdrop, seven were lost to anti-aircraft fire. The bold plan to attack in four places to maximize surprise, rather than concentrating on one, seemed to have failed, although the reasons were unknown to the Germans at the time.